Experts who have spent the last year forecasting Covid-19 transmission across the US are now considering scenarios for the spread of new, more infectious strains of the coronavirus.

At the same time, the US continues to lag in surveillance for coronavirus variants, despite having among the most well-developed genomic sequencing infrastructure in the world.

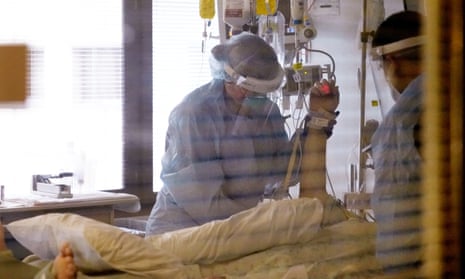

The warnings come as the US appears to have crested a devastating winter wave of infections, which at one time saw more than 300,000 new infections and 4,000 deaths a day. Even though daily infections have more than halved from the peak, with death rates expected to drop soon also, the threat of the more infectious variants has some considering the possibility of a fresh surge.

“It’s a grim projection, unfortunately,” said Ali Mokdad, professor at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, one of the leading academic forecasters of Covid-19. “I’m concerned about a spike due to the new variant and the relaxation of social distancing,” he said. “People are tired. People are very tired.”

Forecasters still do not consider this the most likely scenario, nor do they see it as the worst-case scenario. But the addition of the model is a recognition of how dangerous new variants can be, even in an environment where hospitalization and death rates are expected to decline.

IHME’s “rapid variant spread” model predicts total deaths could increase by 26,000 over the most likely scenario by May. Such a forecast would result in a total of more than 620,000 Covid-19 deaths by that time.

Notably, the most accurate are often “ensemble” forecasts, which draw in many individual projections. The ensemble forecast published by the CDC makes a prediction only through 27 February, when it estimates up to 534,000 deaths could occur. IHME also estimates universal masking could save 31,000 lives.

On Monday, the US surpassed 27m confirmed coronavirus cases, with the country’s death toll nearing 465,000. Both figures are by far the highest in the world, according to the John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

The most well-understood variant of concern is the B117 strain, first detected in the United Kingdom. B117 is believed to be as much as 50% more transmissible and to be now circulating in the US, where 541 cases have been found in 33 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Studies are still being conducted on how B117 may affect the effectiveness of the two vaccines currently authorized in the US, from Moderna and Pfizer. Another variant from South Africa, called B1351 and recently found in South Carolina, does appear to reduce vaccine efficacy. New strains can also affect the effectiveness of some of the only treatments for Covid-19 patients, including monoclonal antibodies.

“If the new variant makes the vaccines less effective and new variants come up, we could have a surge in the summer,” said Mokdad.

Variations in how a virus replicates genetic materials are expected and a feature of how viruses evolve over time. This can be especially true of viruses like the coronavirus, whose genetic material is made of ribonucleic acid (RNA), because these viruses lack some “proofreading” mechanisms that reduce mutations. Most changes are benign – like a typo in a paper – and do not change the functionality of the virus.

But rampant, widespread global transmission has given the coronavirus millions upon millions of chances to replicate, and change as it does. Among the random, inconsequential typos are rare changes that alter how the virus behaves.

For example, B117 is believed to be more infectious. A more infectious virus is a more successful virus, and through thousands of new infections, natural selection will favor the successful virus, eventually replacing previous, once-dominant strains.

“A small percentage of a big number is still a big number,” said Emily Bruce, a virologist and investigator at the Center for Immunology and Infectious Disease at the University of Vermont’s Larner College of Medicine. Variations are “a function of the number of people and number of infections and cycles of replication the virus is going through”.

Scientists can detect these changes using next generation sequencing technology. This technology was used in spring 2020 to show the origin of a majority of Covid-19 cases in New York were actually from Europe, not China as the Trump administration insisted.

While some labs were pursuing specific projects using this technology, a national, systematic surveillance program was never put in place. It wasn’t until November that the CDC began regularly receiving samples from Covid-19 patients from state labs. It now processes roughly 750 samples a week. The US currently ranks 43rd in the world for Covid-19 genomic sequencing, despite having well-developed genomic sequencing infrastructure.

“There’s people who’ve done spectacular work here, but it wasn’t funded and strategized in a national way the way leaders in the field did this,” said Bruce.

The cost of genomic sequencing has dropped precipitously since the early 2000s, when ambitions to map the human genome cost $100m, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute. Today, sequencing one human genome costs about $1,000.

Doctors hoped to start using this advanced technology, called next generation sequencing, to tailor treatment to specific patients. That field is touted as “precision medicine”, a way for doctors to tailor treatments to specific patients.

But, as in many other aspects of American life, the coronavirus pandemic has revealed weaknesses in the system. Experts said, in large part, the lack of a national surveillance program for coronavirus variants came down to lack of funding.

“It costs a certain amount of money to sequence each strain, and I am a brand new investigator, I don’t have the money to pay for that,” said Bruce. “And people’s insurance isn’t going to pay for that because it’s important information, but it’s not going to change an individual patient’s care.”

Sequencing an RNA virus is less expensive than sequencing a whole human genome, because they are far less complex organisms, but it is still far more expensive than a typical coronavirus test, running in the hundreds of dollars. That is because expert labor is needed to interpret the results – including molecular biologists and virologists like Bruce.

“This virus is here to stay,” said Mokdad. “We’re not going to reach herd immunity, simply, we’re not going to reach it. It’s going to be seasonal, and it’s going to be like the flu, and we’re going to need to be ready for it,” he said.

That leads to another potential need from vaccine-makers – vaccine updates to enhance immunity to new variants. Already, Moderna and Pfizer are working on “booster shots” for Covid-19 variants. Experts now recommend double-masking to protect against the virus, alongside more vigilant social distancing.

Together, these developments have made Mokdad certain of one outcome: “I’m 100% sure in winter [2021-22] we will have a surge – but it will slow down our decline. But I’m convinced it will happen.”