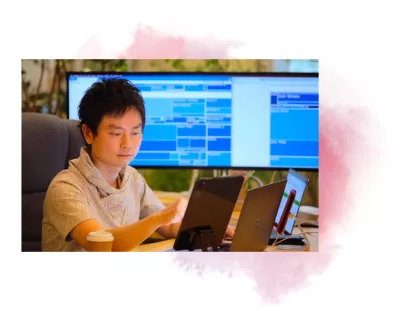

Dr. Shuhei Nomura: Collaborating in Japan

Published May 3, 2022

"Health, life, and safety research constitutes nothing more than desk theories, unless we properly grasp the situation occurring on the ground." - Dr. Shuhei Nomura, Associate Professor, Keio University and Assistant Professor, University of Tokyo, GBD collaborator

We work in global health, and many of us share a passion for travel and discovery. Where are your favorite places to visit?

Kolkata, India and London, United Kingdom. Kolkata was the first place outside Japan that I ever visited; the moment I stepped off the plane at the Kolkata airport, everything I saw, and even the air I felt, was new, and I vividly remember how excited I was. I was only in Kolkata for a week, but after that, I wanted to experience more of the world. London was the first place I have stayed abroad for a long time, and it was during my time as a doctoral student at Imperial College London that I fully enjoyed the pleasure of learning about and experiencing the deeper aspects of the culture and values of a place outside Japan.

What do you work on for the GBD and how does the GBD support your work?

I am involved in a wide range of GBD activities focused on Japan. My work includes collecting data, validating preliminary estimates, providing Japanese translations, and communicating with the Japanese media about GBD publications. In 2017, I led a study alongside more than 30 experts, including local Japanese government officials, to identify health disparities in Japan by estimating the burden of disease and the associated risk factors at the subnational level. Moreover, I have been actively promoting the concept of the “burden of disease” to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Japan for use in the national health strategy and global health policy and diplomacy. GBD is a very powerful tool for providing evidence that supports advocacy as well as providing policy recommendations to politicians and stakeholders.

What are you working on outside of the GBD?

Currently, I work with national and local governments in Japan to control the COVID-19 pandemic in each prefecture. Users input their physical conditions and living environments through social networking services; my team and I then analyze the users’ information to perform disease control measures such as preventing infection spread in local areas and implementing social distancing measures. Furthermore, I supervised the launch of the Japanese version of COVID-19 Public Forecasts, developed by Google for the United States, which has been used to inform policy at all levels. At the request of the MHLW and in cooperation with the National Institute of Infectious Diseases of Japan, I am leading the calculation of the mortality burden from COVID-19 in Japan and have launched a visualization tool called Excess and Exiguous Deaths Dashboard in Japan.

Most recently, I have been appointed to the Global Nutrition Report’s expert panel, which tracks and evaluates country commitments to the Nutrition Summit (a high-level meeting on food and nutrition). Through this, I will provide independent, data-driven assessments to demonstrate the current state of the world’s nutrition and participate in creating a big-picture vision for improving nutrition.

As a member of the Special Commission on Japan’s Strategy on Development Assistance for Health, I am also working to improve the transparency and accountability of the Japanese government’s global health contribution, which has tended to be opaque in the past. I support the work of the committee by clarifying and visualizing the flow of funds for Japan’s international cooperation in the health sector, including the official development assistance (ODA). In addition, I work for several policy advisory consulting organizations to drive progress and innovation in global health. My role includes evaluating country ODA policies, supporting the strategic development of global health organizations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and making recommendations to politicians and stakeholders.

What inspires or excites you most about your work and why?

I find it exciting to have intellectual discussions with local practitioners and policymakers on topics that contribute to both field practice and policy development. I believe that today’s researchers require a practical perspective to determine and demonstrate bottlenecks for specific issues, and to understand how to put their conclusions into practice.

For example, immediately after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, I visited elder care facilities in the affected areas, tracked evacuees, collected data, and demonstrated that the mortality risk among older people had increased significantly due to the evacuation. The findings of this study were cited in several international reports, warning that the evacuation of older people in the event of a radiation accident or natural disaster may pose more risks to life than the direct effects of the disaster itself. Japan’s nuclear emergency preparedness and response guideline, which was formulated after the disaster, was also revised to include a warning about the health risks associated with the evacuation of older people and other people who need care. It is a great pleasure to be involved in policymaking in Japan and the international community and to be able to give back to society through such practical research and advocacy work.

Do you have a favorite story from your work life?

In March 2020, many people from local Japanese governments, private sectors, academia, etc. gathered to launch COOPERA (COvid-19: Operation for Personalized Empowerment to Render smart prevention And care seeking) with the aim of “doing as much as we can with approaches that are possible right now.” Through SNS, COOPERA provides individualized support for self-care, suggests preventive behavior to avoid infection events, and captures the epidemiological situation of COVID-19. Because of the urgency of the situation, it was my responsibility to form an academic data analysis team in just a few days. Therefore, I first approached a classmate from graduate school who had a different specialty and who I trusted absolutely. To my delight, the friend readily participated in its launch, and I asked him to find a colleague using the same method. I managed to assemble a dynamic team of mainly young people in their 20s and 30s, half of whom have doctorates in different areas. After intense day and night online discussions, COOPERA was successfully put into operation just two weeks after the project was conceived. Throughout this period, I kept all communication devices and apps running and tried to respond immediately to all communications at all times. I realized that I am blessed with many wonderful colleagues and was impressed by the enthusiasm with which the team worked together to implement the project.

What achievement are you most proud of?

In 2014, in recognition of my disaster reconstruction work following the Fukushima disaster—ranging from grassroots activities in local communities to policy advisory activities for government agencies and international organizations—I was awarded the “Japan’s Symbol of Tomorrow,” a highly competitive and prestigious award given to people under the age of 35 in honor of their pursuit of health innovation. I was granted an audience with the then-Majesties, the Emperor and Empress of Japan, at the Imperial Palace, where I had the opportunity to talk about the existing situation at the disaster site in Fukushima Prefecture.

What motivates you?

I have always been motivated by the desire to return the outcomes of my research to society. In addition to the reconstruction work following the Fukushima disaster, I have had the opportunity to experience support for refugees and displaced people in the former Yugoslavia, disaster prevention support in Tajikistan, and support for AIDS orphans in South Africa through internship and volunteer work. All these experiences made me realize firsthand that health, life, and safety research constitutes nothing more than desk theories unless we properly grasp the situation occurring on the ground, scientifically verify the issue, and put the research findings into practice.

What are the most important lessons you have learned from your work/area(s) of research?

My experience has led me to believe that it is important to understand the code of conduct, which is often a problem in disaster research. It is not uncommon for many groups to repeatedly conduct research after a disaster with disparate objectives, ignoring the feelings of disaster victims and causing anger and fatigue among the local people.

I saw this occur frequently in the affected areas after the Fukushima disaster. The disaster occurred just one month before I started my master’s program at the University of Tokyo, and my mentors at the time taught me how to properly return the research outcomes to the people in the affected areas. The first thing I did was to try to understand disaster victims’ feelings while I was volunteering for several local health checkups conducted by local governments. Sometimes I drove 300 km from Tokyo to the affected area then slept in a rented car; at other times, I lived in the area for several weeks to help with administrative work at affected hospitals. What I valued most in my disaster research was listening to “the voices from the field.” I have published more than 50 papers from Fukushima, and for each of them, I prepared explanatory notes in Japanese, distributed them to local governments, and explained them to the people concerned. This experience has become the foundation of my career as a researcher. Even now, 10 years after the disaster, I continue to do the same.

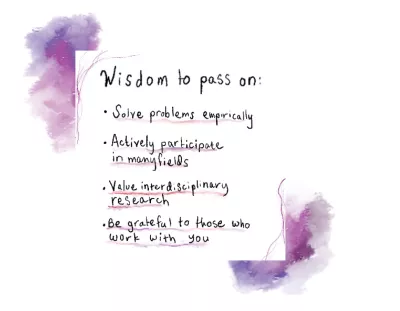

For generations who stumble on this interview years from now, is there any wisdom you’d want to pass on to them? What would you want them to know?

I am still learning every day, but if there is anything I can tell the next generation of researchers from my short career experience, it is the following two points.

- Value the practical perspective of solving problems empirically, and value the attitude of returning research outcomes to society.

- Learn various schemes by actively participating in many fields without being bound by a specific specialty, and value interdisciplinary networks with the same generation in different fields. Moreover, be grateful to those who provide you with such opportunities and those who work with you.

The collaborator spotlight project showcases individuals within IHME’s expansive network of over 7,000 global collaborators who conduct the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) and its affiliated research projects. This series of interviews gives an inside look at the people behind the research, as they discuss their current projects outside of GBD, book recommendations, and more.