IHME COVID-19 insights blog

Published December 16, 2022

In December, 2022 IHME paused its COVID-19 modeling. Past estimates and COVID-related resources remain publicly available via healthdata.org/covid.

To hear the latest on COVID-19 and other topics in global health, visit our Global Health Insights blog.

IHME director and lead modeler Dr. Christopher J.L. Murray shares insights from our latest COVID-19 model run. Explore the forecasts: covid19.healthdata.org.

Our COVID-19 resources:

- Policy briefings (projections explained) for 230+ national and subnational locations | Explore the briefings

- Updated estimation methods for total and excess mortality due to COVID-19 | Read the methods

- COVID-19 model briefings delivered to your email inbox | Sign-up for emails

- Our COVID-19 publications | View publications

- Questions about our projections? | Read our FAQs or email us at [email protected]

- For media inquiries, please contact [email protected]

October 24, 2022

Key takeaways:

- New Omicron subvariant XBB does not appear to have immune escape with BA.5, meaning individuals who were previously infected with BA.5 will maintain their immunity against the new subvariant.

- New analyses also show all subvariants of Omicron appear to be less severe than previous variants.

- The surge in Germany may be due to subvariants BQ.1 or BQ.1.1, and will likely spread to other parts of Europe in the coming weeks.

- We predict winter seasonality in the Northern Hemisphere will bring more infections, but not a large increase in deaths.

- New research on long COVID shows it has affected millions worldwide and is more common in women than men.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

In this week’s analysis of COVID from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, we have spent a lot of time in the last few weeks recalibrating our model to reflect the differences between waves of variants for the infection-detection rate, the infection-hospitalization rate, and the infection-fatality rate. And when we put that together with all the new data that we’ve seen in the last three or four weeks, our attention gets drawn to two key areas.

New subvariant XBB

First, the XBB-related surge in hospitalizations in Singapore, and it’s a pretty rapid increase in hospitalizations over a short period of time. Very nice analyses out of Singapore, telling us that it’s more transmissible. But the good news is that also, those analyses suggest there’s no immune escape with BA.5.

In fact, people who have been infected in the last three months, presumably with BA.5, had essentially almost no incidence of XBB. So that’s really good news in terms of its potential for global spread and impact. It still, however, means that those individuals and communities that have had low past Omicron infection, particularly BA.5, are at risk for the surge.

The other good news out of Singapore is that it doesn’t seem to be more severe – if anything, slightly less severe. Our recalibration exercise has confirmed what we thought almost 10 months ago, that Omicron, including BA.5, remains more than 10-fold less severe than previous waves of the COVID pandemic. And that has continued for all these Omicron sub-lineages so far.

Surge in Germany and predictions for Europe and the Northern Hemisphere

The other area of concern is the really rapid increase in hospital admissions, as reported in Germany – higher rates of hospital admission now than at any time previously in the COVID epidemic. The last couple of days it looks like COVID admissions may be coming down, but of course, there’s this question of lags in reporting. So we’ll wait and see if that holds true in the next three or four days.

But the increase has already been quite large. We should expect that to spread, probably due to BQ.1 or BQ.1.1 – not 100% sure because of lags in reporting of the sequencing data – but it should spread to other parts of Europe, we suspect. Again, we don’t have good data at all separating out admissions due to COVID as compared to admissions with COVID, and so we’re not really sure how consequential this big surge in Germany is and how consequential it will be for the rest of Europe.

We do expect that the sort of smaller, slow increases in the northeast of the US, as an example, are the beginning of people going back to school, winter seasonality starting to kick in, so we continue to expect considerable increases in infections through the Northern Hemisphere winter, but without major increases in deaths due to COVID – but quite a number of deaths with COVID, and same for hospitalizations.

So until we learn more about the German surge and whether it’s associated with more severe disease, we remain reasonably, cautiously optimistic that the winter will have more infections, maybe not so many cases because of the great reduction in the infection-detection rate, and we should see quite a few hospitalizations with COVID, but not so many due to COVID.

Continuing zero-COVID strategy in China

China is the last big question mark, where there have been mixed signals from different groups in China about whether or not the zero-COVID strategy would continue. President Xi Jinping has made it clear, at least publicly, that they plan to continue with the zero-COVID strategy.

And so when we build that into the models, we don’t see a huge surge in China. But given the large number of susceptible individuals in China and the very low levels of past infection, the potential for an explosive epidemic always remains there, especially if the zero-COVID strategy was backed off even a little bit within China. So that’s the sort of main pictures that we see around the pandemic or COVID transmission in different parts of the world.

There are some interesting, but too early to tell, signals in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa that maybe cases are also going up there, but that could also be related to the data challenges that we’ve seen throughout the pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa.

New findings on long COVID

Now, the last thing to comment on is we published this week in JAMA, our analysis with many collaborators of all the cohorts that were available on long COVID, and put those together to get an overall picture about long COVID.

And just to reiterate the key findings there, the risk of long COVID is very much related to severity of disease, much higher if you went to hospital, even higher if you had to go to the ICU. Long COVID is more common in women than men, and it’s quite low-risk in children. And with the milder variants, we also expect to see a lower probability of long COVID.

Despite that, we’re seeing 5% or 6% of individuals having long COVID symptoms at three months. That fortunately drops down to about 1% at 12 months. But if you take the huge volume of COVID infections in the world, those numbers do translate into a very large number of individuals globally who will be suffering at three months from symptoms of long COVID and many millions suffering even at 12 months with symptoms of long COVID just because of the incredible ubiquity of COVID infection. Even though the probabilities are not that high, individual by individual, they add up to a big toll on society.

September 16, 2022

Key takeaways:

- Long COVID is a real problem. It affected 17 million people in the European region in 2020 and 2021.

- The more severe a case of COVID is, the higher risk of developing Long COVID. Adults are at higher risk than children.

- About 6% of people with COVID still had symptoms after three months and 1% had symptoms after a year.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

We are very interested in the evidence base around Long COVID and have had a number of initiatives running for about a year and a half, trying to get the various researchers around the world that have cohort studies on Long COVID, getting them to work together and pool that information and figure out what the actual risks of Long COVID are.

And there are future studies that are planned and will be coming out about that joint work with many groups. This week we used those insights with the World Health Organization European Regional Office and put out an analysis of what the implication of the cohort studies were for the European region. [We found] 17 million people in 2020 and 2021 with Long COVID, where Long COVID is defined as symptoms running three months or more and, at the heart of it, it does point out that Long COVID is a real problem.

Read the press release from WHO

It's quite considerable numbers globally and by region. And what we do know from the examination of the cohort studies is that it seems to be a higher risk of Long COVID the more severe your case was, so much higher probabilities of Long COVID if you went to the ICU or you were hospitalized, than if you had mild symptoms.

It's also a higher risk in adults than in children. And the risk, there's some people who have, by definition three months of symptoms. And then there are still some people in the cohort studies that have symptoms at 12 months. So some Long COVID can be very long indeed.

The numbers, roughly speaking, are running about 6%, everyone coming, having had COVID, having symptoms at three months, of Long COVID and 1% having symptoms at the end of a year.

Given the huge volume now of Omicron infection in the world, we don't have the implication of the number of patients with Long COVID. It could be very large and could be a real burden on society and on health systems, and on the individuals who are affected. But we don't have the same cohort data available yet specifically, or very much less, specifically about Omicron.

Given the general relationship between severity and risk of Long COVID we hope that those probabilities I was quoting for Long COVID should be somewhat lower for Omicron.

Regardless, it is a big issue and it is important to some of the initiatives that we've seen in the European region of coming up with strategies to help patients manage Long COVID symptoms and I'm sure we will see similar discussions around Long COVID in other regions of the world as the epidemic continues.

September 12, 2022

Key takeaways:

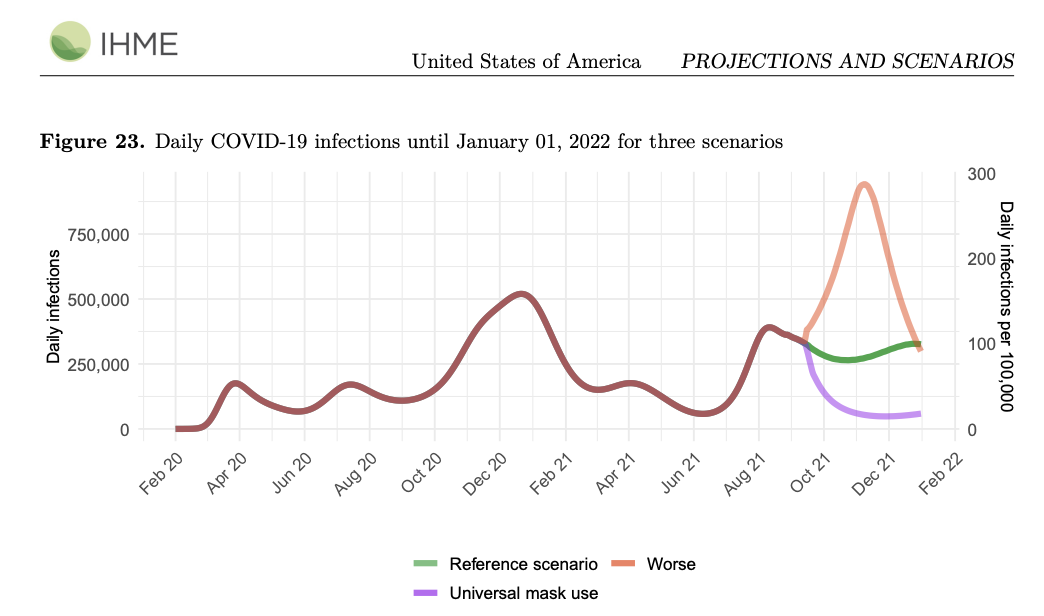

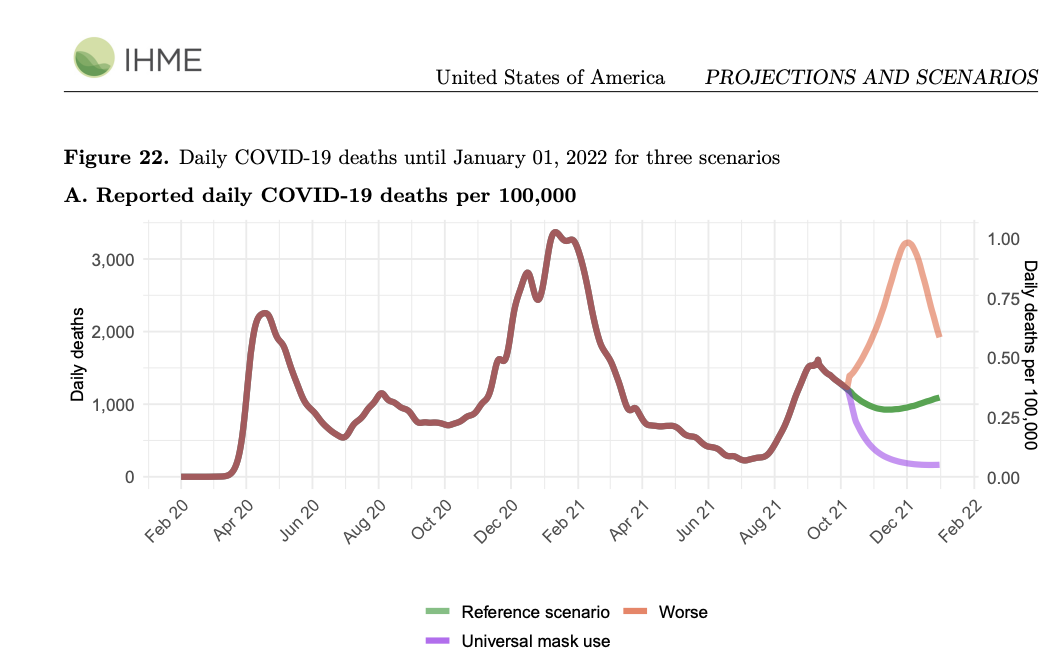

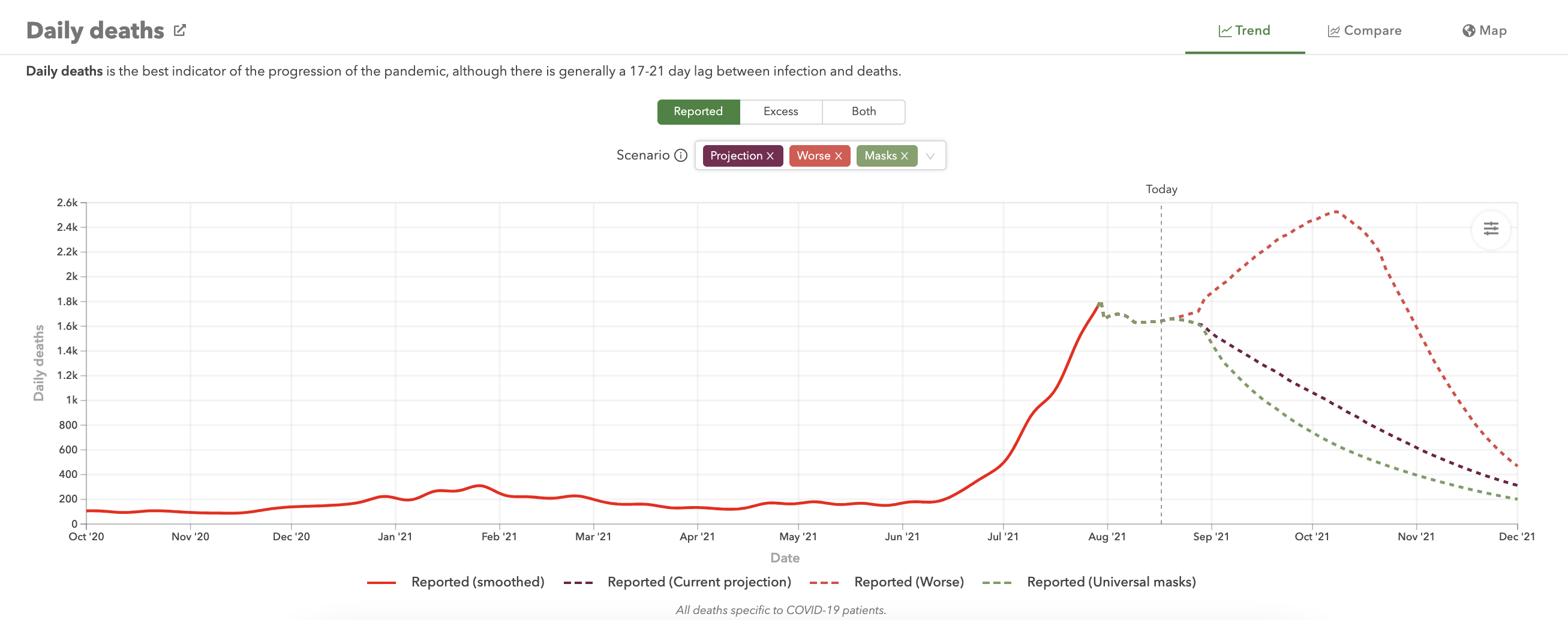

- New projections through January 1: infections will drop until October and then increase in the winter.

- Current projections show a relatively low death toll, but a new variant could change that.

- Our recommendations:

- Maintain and improve surveillance for new variants.

- Encourage boosters.

- Provide access to antivirals for older and high-risk individuals.

- Determine which social distancing mandates have the greatest impact if a new, more severe variant emerges that warrants their use.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

New challenges with modeling

In this week's release on modeling the COVID-19 epidemic, we've got updated forecasts out to January 1. The analysis proves to be quite challenging the farther into the epidemic we go, because the balance of how many people are able to get infected and thus likely to transmit the virus and sustain transmission is incredibly driven by two factors: first, the pace at which immunity wanes, whether from vaccination or recent infection.

Two aspects of that, 1) the pace at which immunity wanes for infection, which is faster than immunity waning for severe disease, so we get these differential effects on waning, and then 2) the degree of cross-variant immunity between sub-variants of Omicron. So, how much can BA.5 infect people who have been infected previously with BA.2 or BA.1?

Those are not, especially for BA.5, well understood. There are not that many published studies on waning immunity and cross-variant immunity, so we have to try to infer that from neutralizing antibody studies, as well as the behavior of BA.1 and BA.2 compared to the Delta variant. So that generates quite a lot of uncertainty, and as we try to fit each model to the available data for each country, it is a harder challenge. It is a more brittle analysis.

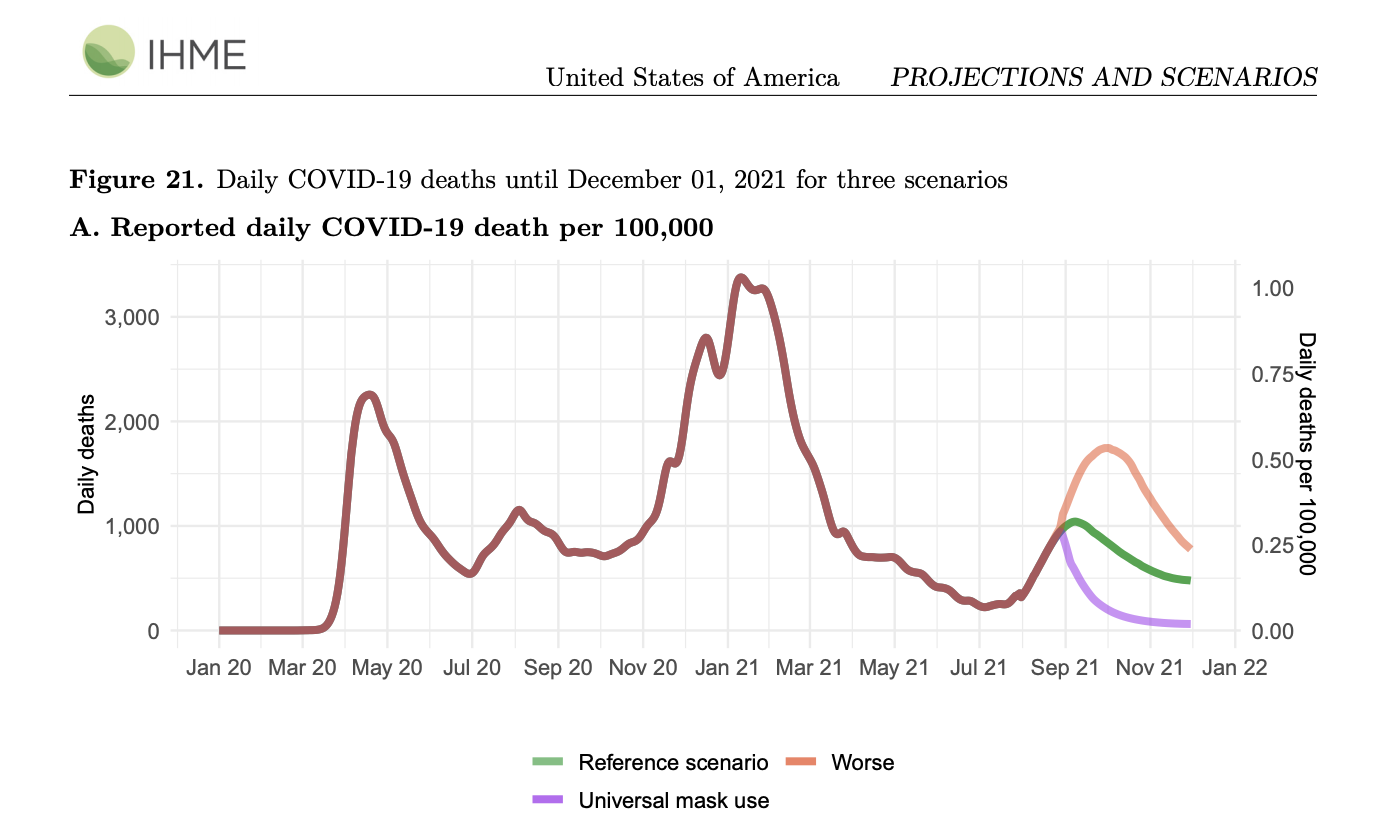

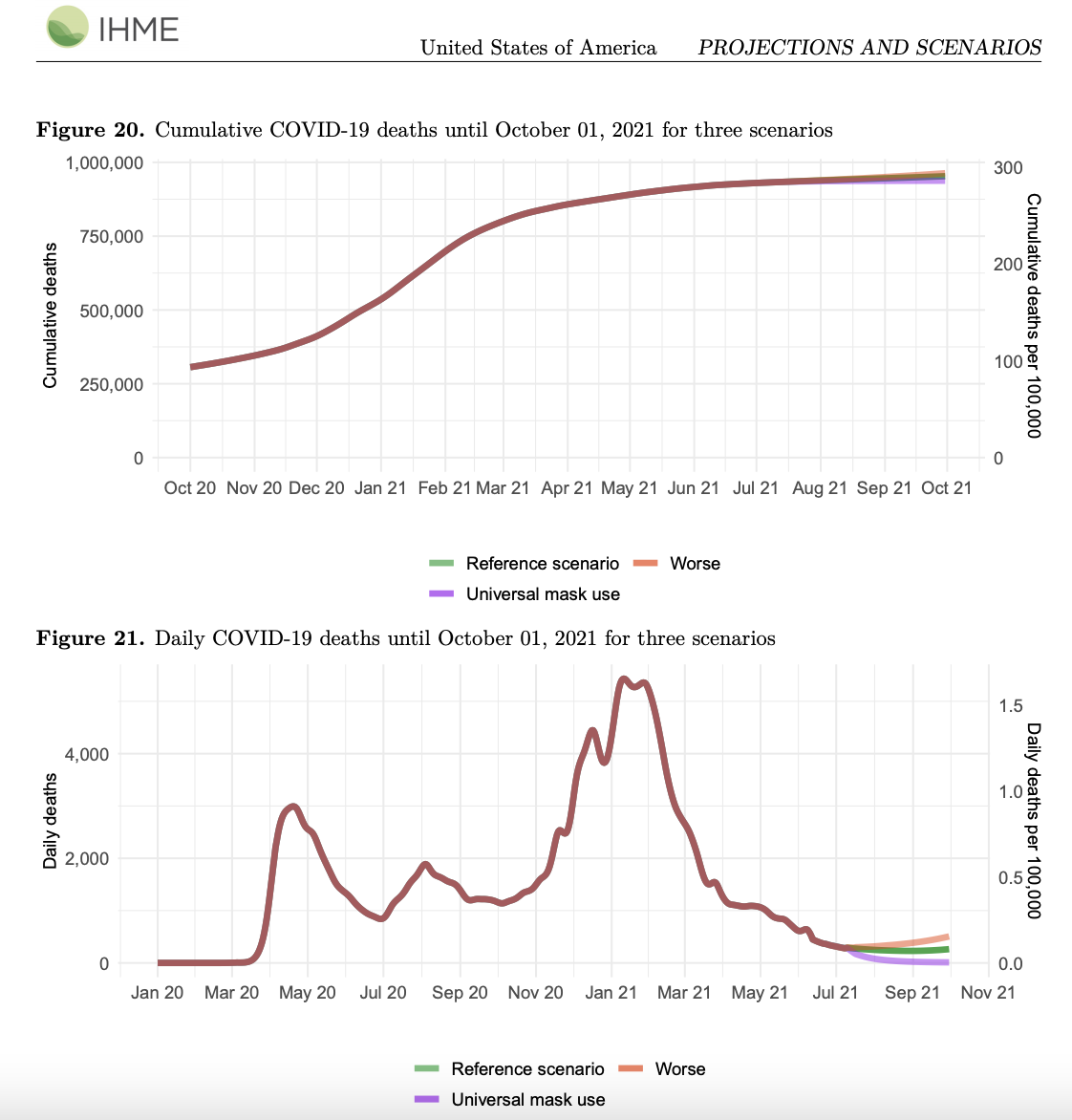

The latest results: a winter increase in infections but not reported cases

We've been able to do that for all locations, and what we see in those forecasts is that for many places in the world, particularly the Northern Hemisphere, outside of China, we expect infections to keep dropping as they have in recent weeks in most places, and then start to go back up in October through to the end of the year.

The increase of infections – and this is in the absence of any new variant, so this is really just BA.5 – the increase in infections could be quite large in the winter. But the infection-detection rate, the fraction of infections that get reported as a case in official data, is now down to an incredibly low level. In some parts of the Northern Hemisphere, it's below 2%; in others it may be as high as 5%.

That means that this big increase in infections we are modeling for the fall and the winter will not translate into big increases in cases, but we may see a larger increase in hospital admissions where COVID is present.

Because of routine testing of all hospital admissions in most countries, we see a bigger increase in some places – Norway is a great example of this –- in hospital admissions – this was the case with BA.5 over the summer – than in reported cases. We expect that phenomenon to continue, given the current rules around universal testing for hospital admissions, where hospital admissions are essentially a measure of community transmission, as opposed to a measure of severe disease with COVID, since there are a lot of incidental hospital admissions, people coming in for some other cause who happen to be COVID-positive.

Current projections show relatively low death toll, but a new variant could change that

Because of the sustained low infection-fatality rate that we're seeing for BA.5 due to vaccination and past infection, and access in some jurisdictions to antivirals like Paxlovid, we expect not so many deaths, only just over 50,000 in the Northern Hemisphere and a larger amount in the rest of the world. We expect that the death toll to be quite modest through to January 1.

If a new variant comes along, all bets are off as we've seen with the emergence of Omicron this year, or even a new sub-variant where there's considerable reduction in cross-variant immunity.

China's zero-COVID strategy continues

The one exception to this description of generally not a high level of threat around the world in terms of severe disease is what will continue to play out in China, where the zero-COVID strategy continues to be pursued and we continue to see renewed outbreaks in different provinces. If the Chinese leadership decide to back away from the zero-COVID strategy, we would see a very large outbreak of Omicron, and, given low vaccination in the 80+ population in many provinces, we would see quite considerable deaths as we saw in Hong Kong earlier in the year.

But that's very much a function of what the government will do. They've committed so far publicly to zero-COVID, so we don't expect a big toll yet. But that could change through the fall as the economic consequences of zero-COVID continue to unfold.

Our recommendations for managing the next phase of the epidemic

That's our roundup of what's happening around the world. In terms of strategies to manage it, number one is to stay vigilant for governments and to maintain surveillance, maybe improve it, do more what the UK has done with the Office of National Statistics Infection Survey, so you know about true transmission. And to take a worldwide view of surveillance, so when a new variant or sub-variant shows up, the world is ready to act if needed.

Secondly, encourage boosters in those who are due for a booster as immunity does wane even for severe disease.

Thirdly, make sure those who are older or at high risk get access to antivirals as needed.

And then, a very cautious approach to trying to look at the evidence to date to figure out which of the social distancing interventions had the biggest impact, so that in a worst-case scenario, if a severe variant shows up with considerable immune escape, we can use those social distancing mandates and measures that are most likely to be beneficial and minimize the economic, educational, and social disruption in the future.

July 22, 2022

Key takeaways:

- COVID-positive hospital admissions are rising in the US. However, it is unclear whether the hospitalizations are due to COVID, or if individuals tested positive after being admitted for other reasons.

- We remain optimistic that there will not be a large amount of severe COVID, due to widespread use of Paxlovid and the likelihood of many hospitalizations to be incidental infections.

- Our recommendations:

- It is not necessary to implement mask or social distancing mandates at this time.

- National surveillance systems should track the underlying cause of hospital admissions.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Rising COVID-positive hospital admissions in the US

In some jurisdictions in the US, there are rising reported hospital admissions with COVID, and in some cases, examples of rising deaths. This has caused considerable policy discussion about whether it is time to reinstate mandates, such as the consideration of mask mandates in LA County.

The challenge that we have in understanding what's happening with BA.5 is that this is a very common infection. We see lots of evidence of considerable transmission in the community that is not translating into a big surge in reported cases, largely because we believe there is so much rapid antigen testing at home.

Many COVID hospitalizations are incidental

We do see rising numbers of hospital admissions, and the challenge – as we've spoken about before – is distinguishing incidental, that is people coming to the hospital with some other problem, who happened to be COVID-positive when they get tested, from true COVID admissions. Unfortunately, in this country we don't have data on COVID admissions where they are positive for COVID and that's the reason for admission. Some hospital systems are reporting this.

There are reports from USC, for example, in LA County, that fully 90% of hospital admissions are incidental, meaning it is quite possible that we don't have reason to be that concerned about BA.5 transmission.

Read more in Nature »Heart disease after COVID: what the data say

Unlikely to be many cases of severe COVID

It could well be, because of high levels of immunity in the population from vaccination and from past infection, and quite widespread use of Paxlovid, if we look at the data in the US, that there isn't really cause for concern that there's going to be a large amount of severe COVID. This means, perhaps, that it is not the time, at this point, to be considering imposition of new mandates such as mask mandates or social distancing mandates.

The situation globally

This is a phenomenon we're seeing in other countries as well – it's not unique to the United States. There are reports from New Zealand, for example, in the last few days, of a marked increase in daily deaths. And again, this challenge is there, as well as in many countries in Europe – Norway is another example – where incidental from underlying is not being distinguished. It could well be just that BA.5 is a very common infection.

The only way we're going to resolve this for the future is if national surveillance systems make the effort to track hospitalizations and distinguish them by the underlying cause of admission.

We remain reasonably positive and optimistic about the course of BA.5 in the US and elsewhere. We do see early signs that it may have peaked already in the US and is starting to come down – that's not true for every state, but in general it does seem to be following the course that we've seen in other countries around the world.

July 20, 2022

Key takeaways:

- BA.5 is surging around the world, particularly in North America, Latin America, and Europe.

- We anticipate waves to last around four to six weeks, based on other locations’ experiences.

- There are several new challenges for accurately tracking the pandemic:

- More people are using at-home tests and not reporting infections to public health authorities, making it difficult to gather accurate case counts.

- Countries have different requirements for COVID testing upon hospital admission, leading to variation in rates of hospitalization due to COVID, compared to incidental cases.

- Our policy recommendations:

- Encourage booster shots.

- Make antivirals available to all, particularly those in low-resource settings.

- High-risk individuals should consider social distancing and masking as transmission increases.

- Do not focus on getting vaccines to those who have never been vaccinated.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

BA.5 surges around the world

In this week’s COVID update from IHME, we’re looking at the surges around the world – particularly in North America, Latin America, and most of Europe – that are traced to the combination of mobility levels being above pre-COVID levels, mask use globally down to 16% or less, and of course the BA.5 subvariant of Omicron.

Interpreting the data has new challenges

It is becoming increasingly challenging to make complete sense of the COVID-19 surges in different countries, as we see very different biases in different countries coming into reported cases, hospital admissions, and reported deaths.

For reported cases, we're seeing very modest to no increase in some countries in Europe, as compared to hospitalizations. Same in the United States. And we believe that's because of the widespread use of rapid antigen tests at home and in most countries people not reporting that to the public health authorities. They don't get into official case numbers.

In contrast, for hospital admissions – if you want an extreme example of this disconnect, look at Norway, where hospital admissions have gone up dramatically and yet cases have gone up only slightly. But for hospital admissions, most countries have required COVID testing for all patients, at least most high-income countries, meaning that you detect a quite substantial number of individuals who have COVID, but have gone to hospital for some other reason. We tend to call these "incidental" COVID admissions.

The degree to which there will be incidental COVID admissions depends on how much transmission there is broadly in the community. So we should expect under Omicron, the problem of incidental hospital admissions is dramatically larger than with a much more severe variant, such as Delta in the past, where there was less transmission in the community, and those coming to hospital who were COVID-positive were much more likely to be there simply because of symptoms of COVID.

So, challenging interpretation. And if you want to have a contrast to Norway, look at Mexico, where the increase in reported cases is dramatically higher than the increase in hospital admissions. We don't know if that's because there isn't the same testing requirement, of universal testing for COVID for hospital admissions, or if there is less home use of tests. Either way, it's becoming quite a bit harder to make sense of the available data.

Should we be very concerned about BA.5?

Probably not. In the places that started earlier – South Africa, Portugal – that had their BA.5 waves begin before other locations, we've seen from the beginning to the peak, it lasts about four to six weeks. So in many cases where countries are three-four weeks into these surges, we do think that we will see – and the models tend to back up that observation – we do expect to see peaks coming in the near future. Meaning that there isn't a reason to be particularly alarmed about BA.5,

Our long-range models also suggest in the Northern Hemisphere that we may – in the absence of a new variant that changes the whole story – we might expect to see a further winter or late fall Omicron wave start up again in October, and that would be a pattern that we saw in 2020 and 2021.

Whether that happens depends very much on this balance between waning immunity from prior vaccination – so whether or not people get a fourth booster in places where they have access to that, whether they want a fourth booster – versus waning immunity from infection and the protection provided from infection with Omicron for either other subvariants or future variants. All of that means to say that it's possible that we have a late-fall surge again from Omicron because of waning immunity.

Government policy recommendations

The strategies available for governments right now are less on getting people who have never been vaccinated, vaccinated. The data out there suggest very few people anywhere in the world who want to be vaccinated have not been, even in low-resource settings. As opposed to the available strategies, which might focus more on getting those who are willing to be vaccinated, who have been previously vaccinated, getting a further booster to enhance their protection against severe disease as that also wanes over time; broader use of antivirals, particularly in low- and middle-income countries; and then, for those individuals who are at particularly high risk, consideration of social distancing and masking as transmission in your community goes up.

As a backdrop to all of those strategies, the thing that we are learning, that is, two and a half years into this pandemic, is just how important surveillance is. Paradoxically, in many ways, the data stream that we have today is worse than a year ago because of some of the issues that I started with in this video about home testing, and different definitions of incidental versus underlying COVID for both hospitalization and death. So, very challenging on the surveillance side, but absolutely critical that we keep monitoring the pandemic and trying to do it in as comparable a fashion as possible, and particularly keeping track of new variants. That's our roundup of what we see in our analysis this week in the release of our new forecasts.

June 24, 2022

Key takeaways:

- In the United States, COVID is currently on the decline, but BA.4 and BA.5 could change that. Why?

- Vaccines are less effective at preventing infection from BA.4 and BA.5.

- Previous infection provides less immunity against BA.4 and BA.5.

- Mobility is increasing while mask wearing declines.

- Our recommendations for the US:

- Individuals should get another COVID vaccine and a flu vaccine before the winter.

- States should secure antivirals, especially for those at high risk.

- Governments should continue screening for new variants.

- On a global level, we see a rise in some European countries, including France, Germany, and the UK. The future is still unclear in China, but much of the population remains susceptible to severe infection.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

BA.4 and BA.5 in the United States

In the United States, reported cases, infections, hospitalizations, and deaths continue to decline. This is the pattern we have seen in the northeastern states. It is spreading across the United States, and we project that this will continue all the way until the end of September, when we are expecting another wave.

We are concerned in the United States because of the fast spread of BA.4 and BA.5 – they are escape variants in that it seems from the new studies we are looking at, that the vaccines are less effective in preventing infection of BA.4 and BA.5. They are still very effective in preventing severe illness and mortality, but we are concerned that with BA.4 and BA.5 spreading fast with the relaxation of mandates and with the patterns we are seeing in some European countries where there is a third wave, we are concerned that there is potential here for another bump or increase in cases in the coming months.

We will update our models the second week of July, and we will include all this new information in our models. We will then predict if we see a third wave or not, and how big it will be and how long it will last. In general, we're heading in the right direction in the United States.

Our recommendations for the US

We're expecting a surge in winter, and the focus right now in the United States should be on vaccinating people and getting the booster, and then getting another vaccination before the winter, especially also with flu. We expect that flu season could be bad because we haven't seen flu in the past three years. Our recommendation would be to take another COVID-19 vaccine before winter and a flu vaccine.

Also, our recommendation is for every state to secure enough antivirals in order to make sure they are provided to infected people, especially those who are at high risk, elderly, and people with immunocompromise or with risk factors, chronic conditions, to make sure that we reduce the burden on our hospitals and we save lives.

And, of course, continue screening and making sure that we don't lose track of what's circulating in our country, and if there is an increase in cases due to another variant or pre-existing variant, we take the measures that are necessary to stop the spread of this virus.

Cases rising in Europe

On the global level, what we are seeing right now is a rise in some European countries. We see a third wave, driven mainly by BA.4 and BA.5, and the relaxation of mandates, increased mobility, and low mask wearing. We see the third wave with an increasing number of reported cases, and we see it in France, in Germany, beginning of it in the UK, in Greece, in Israel.

That's a big concern for us because what has happened before in Europe has happened here in the United States, and we could see here in the United States a third wave, especially from BA.4 and BA.5, which are increasing as a percentage of the variants that are circulating.

We know right now from several studies that previous infections from other variants do not provide as much immunity against Omicron and BA.4 and BA.5. Also, the vaccines are less effective in terms of preventing infection. They're still effective against severe illness and mortality for BA.4 and BA.5.

So putting these two together, we are very much concerned that we could see potentially in the United States another wave after the second wave due to BA.4, BA.5, relaxation of the mandates, increased mobility, and low mask wearing.

We will update our numbers in July, most likely the second week due to the holiday, and we will take into account all this new information about the spread of BA.4 and BA.5 in Europe, and the new studies that are showing less effect of the vaccine against BA.4 and BA.5.

Future unclear in China

China remains a big mystery for us – we don't know what's going to happen in China. They're successful so far in containing the virus, but this could change as soon as they change their policy and open up the country because they have had fewer infections because of their success before, their vaccine is not as effective, and much of their elderly population is not vaccinated. So we could see a rise of cases in China as well.

June 10, 2022

Key takeaways:

- Global infections are increasing: Secondary Omicron waves are hitting parts of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Portugal, and the United States. We expect a peak in June, but another surge in the northern hemisphere in September, leading to an additional 120,000 deaths by October.

- Outlook still uncertain for China: Strict lockdown measures continue to be successful but come at an economic cost.

- Policy insights and recommendations:

- Mask mandates in parts of the US are unlikely to have a large effect.

- We must maintain global surveillance to prepare for the possibility of new variants.

- Ensure access to antivirals for vulnerable individuals.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Global infections are increasing

In this week's release from IHME of our COVID forecasts, there are some key observations of what's happening around the world and what we see coming in the models. Globally, we're starting to see the estimated number of infections go up again, and that's driven by secondary Omicron waves in a number of places in sub-Saharan Africa, in a wide array of locations in Latin America, from Quintana Roo, other states in Mexico, through to a number of states in Brazil and all the way in between.

There are also some small increases in states in India, and perhaps most concerning is a quite substantial secondary wave of Omicron in Portugal, related to the BA.5 variant with an associated meaningful increase in the death rate, which we have not generally seen with these secondary Omicron waves in Europe and the northeast of the US. The last place where there is some secondary increase from Omicron is some of the Southern states in the US and some of the states in the Midwest.

Omicron peak is expected in June

Despite these increases, we remain reasonably sure in the modeling that they will peak sometime in June, given what we've seen in Europe with the secondary waves, and what we've seen in the northeast of the US, as well as what we saw with the BA.4-5 wave in South Africa. So we expect these to be short-lived, and to not really alter the global trajectory over the next few months.

An outbreak in China could have a major global impact

The big question mark remains, at the global level, what happens in China. We are assuming that strict lockdown measures will continue through to October, and that they will be, as they have been to date, successful. The reporting of 11 cases today in Shanghai will raise the real questions about the economic toll in China from the strict lockdown policies, but so far there's no indication of a change from the leadership in China.

120,000 deaths expected globally by October 1

Putting all that together in our forecasts, we do not see large numbers of deaths. Although when you add it up around the world, still about 120,000 deaths are to be expected between now and October 1.

The other insight that comes from the modeling is that we expect to see numbers starting to go back up again in the Northern Hemisphere in early September or late September, likely leading into increases – modest increases – in the fall.

Mask mandates in the US unlikely to have a big impact

There is some concern in parts of the US seeing secondary Omicron waves, such as in California, where some mandates have been put back in place, namely mask mandates, for example in Alameda county. As far as we can tell from both the modeling, as well as from the experience elsewhere of the secondary waves, we don't necessarily think that will have a big effect, nor is it necessary given the low infection-fatality rate and given the availability of antivirals, particularly, which should mean that we won't see a substantial increase in death.

Some of the debate about this is getting still obscured, this many months into Omicron, because we are not getting good data that differentiates incidental hospitalizations – people coming to hospital with COVID-19, but that's not the reason for their hospitalization – from hospitalizations and deaths where COVID is the true cause. And without that it's very easy for a highly contagious and reasonably prevalent infection like Omicron to appear like the numbers are increasing substantially.

Continuing surveillance for new variants and access to antivirals will be key

Clearly all of this optimistic view over the next few months at the global level is predicated on the idea that there will not be a new variant that has immune escape and is more severe than Omicron. But of course, that is a distinct possibility and it highlights why maintaining global surveillance – so that if such a variant emerges, the world knows about it as soon as possible – is really crucial, as is preparing for access for the vulnerable for antivirals, because that's likely in the future to be the strategy that will make the biggest difference if a new variant comes along.

June 3, 2022

Key takeaways:

- Global death toll declining: We are now seeing a daily death rate last seen in March 2020.

- China: Zero-COVID strategy continues to prevent major death surges, despite economic consequences.

- Europe & South Africa: BA.2 and BA.4-5 surges have peaked and are now declining.

- United States: Cases are declining at the national level, despite some continued surges at the state level.

- Policy recommendation: Monitor for new variants and be prepared to respond if a new, more dangerous one should emerge.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Daily death toll declining globally

This week at IHME in our update on COVID, we do not have a new model release. That will be coming next week, but we continue to monitor the pandemic. We are really reaching, at the global level, an extraordinarily low level of the impact of COVID. In fact, the death toll at the daily level has now reached the level we last saw around March 20, 2020. We continue to see this very favorable trend down.

Low or declining cases in China, South Africa, Europe, and the US

At the location level, the strict lockdown policy, zero-COVID strategy in China continues to work, although it has great economic effects. The reported cases, as far as we can tell in China, are now down to a very low level. We do expect in our modeling, and continue to expect, that it will be hard to sustain that, given the considerable number of susceptible individuals that are still in China.

Elsewhere, where there were surges related to either BA.4 or BA.5 in South Africa, that's peaked and continues to decline. The BA.2 surges in Europe seem to have all peaked and are pretty much declining.

Here in the US, as we expected, at the national level it appears that case reporting has peaked and is starting to come down, but of course that varies by location. The decline is more in the northeast. Other states are still on the upswing, but nationally we should start to see the numbers come down.

We do continue to expect, in the absence of the emergence of a variant with considerable immune escape on Omicron, that we will see quite low numbers through the next few months.

We must continue monitoring for new variants

Of course, we've learned through the pandemic that the emergence of a new variant can completely change the story in a very quick manner. But for now, it does appear like those countries that are largely returning to pre-COVID levels of interaction and very low levels of mask use will continue to see low or even declining transmission, and certainly low or declining impacts in terms of death, given the slow but steady scale-up of the use of antivirals. So, there are very favorable conditions for the moment.

We do believe it's important to keep up surveillance and to be ready on a country-by-country basis to respond with booster shots, with access to antivirals, and if a dangerous, high-severity new variant with immune escape emerged, to be able to reconsider other actions as well.

May 27, 2022

Key takeaways:

- South Africa & China: Cases appear to have peaked and are now declining.

- United States: The increase in cases is slowing and expected to peak by early June.

- Current recommendations:

- Offer boosters to those who want them.

- Provide antivirals to at-risk individuals who get infected.

- Continue surveillance for potential new variants.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Evidence of BA.4-5 cross-variant immunity in South Africa

This week from IHME, we do not have a new release of our models, but we are continuing to track the evolution of the current pandemic. Of major areas of interest, in South Africa, the BA.4-5 related increase in cases has peaked and is coming down, which fits with the expectation that while there was some reduction in cross-variant immunity from BA.4-5 compared to previous waves of Omicron, it was not very large.

Omicron under control in China

Likewise, we're seeing that the measures put in place in China for strict lockdown, at least according to official data, continue to be successful, with case numbers coming down. Of course, the question will be whether or not there are going to be – as we expect, given the large volume of susceptible individuals – further Omicron outbreaks, and the need for other efforts at strict lockdown in China, still pursuing a zero-COVID strategy.

Cases expected to peak in the US within a few weeks

In the United States, the increase in cases, probably driven by behavioral relaxation, seems to be slowing. There is a spatial heterogeneity aspect to this, but for example, in our own hospital system at the University of Washington, our number of hospital admissions has peaked and is starting to come down, as an example of a place with one of these surges.

So, as we've been expecting for many weeks, we do not think these current increases in the US will lead to large-scale increases in death, certainly, or hospitalization. We should see a peak about the end of May or early June at the national level.

Current recommendations

Pending the emergence of new variants that are more severe than Omicron, the current strategies of continuing to offer boosters to those who would like to get a booster, making sure that antivirals are available for those who are at risk who do get infected with Omicron, and continuing surveillance, are the most important aspects of monitoring the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

May 20, 2022

Key takeaways:

- Regional updates:

- China continues zero-COVID strategy and reports no increase in cases.

- South Africa may be reaching a peak of the BA.4/BA.5 winter surge.

- The United States is experiencing an increase in Omicron cases – likely due to behavioral changes, and possibly due to re-infection with BA.2 – but not an increase in deaths.

- Mandates: We do not expect mandates to be widely re-implemented, outside of zero-COVID policies in China.

- Cross-variant immunity: New research suggests limited immunity against other variants after Omicron infection. However, immunity from vaccination and previous infection does provide strong protection from severe illness and death.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

China reports no increase in cases

We do not have updated models this week, but we continue to monitor the unfolding of the pandemic around the world. Areas of ongoing interest are the approach to zero-COVID in China, which continues. Officially reported cases are actually not increasing, and they're maybe coming down, but stringent mandates are in place in many locations. From experience in other countries, we do expect at some point that Omicron will spread widely in China, but it is very much a question of when – and when the government decides to stop pursuing this zero-COVID strategy.

Cases increasing in South Africa and United States

Elsewhere in the world, we're seeing increases. The BA.4- and BA.5-related and winter-related increase in South Africa continues. It is certainly not as exponential as the original Omicron wave, but it does continue to increase. With some indication, it may be reaching a peak.

In the United States, Omicron continues to increase in a number of states. That increase, again, seems to be like what we've observed in many countries in Europe, related to behavioral relaxation and possibly BA.2 re-infection of people who have had a prior Omicron infection – although it's perhaps easiest to account for through behavioral change.

Mandates not expected to be reimplemented

In neither case, neither what we saw in Europe nor what we're so far seeing in the United States, are we seeing an increase in death, which is very good news. That's likely because there is either vaccine-derived or infection-acquired immunity, so that people aren't fully immunologically naive, and perhaps because of the increased use of antivirals when individuals do become sick, which should have a marked effect on the death rate. We don't, at this point, think that there's reason for large-scale concern and also do not expect, with few exceptions, that there will be implementation of mandates in these jurisdictions, outside the zero-COVID strategy in China.

New studies show limited immunity from Omicron infection

One of the critical factors that do go into the long-range modeling, and even the short-range, is the extent to which Omicron infection provides protection against subsequent new variants, or even sub-variants of Omicron. There was a paper in Nature this week, which is a lab-based paper, based on the immune responses from serum from different types of patients, which suggests that there may be a limited cross-variant protection from Omicron infection.

Read more in Nature »Limited cross-variant immunity from SARS-CoV-2 Omicron without vaccination

We'll really want to wait and see when studies are able to start reporting, from actual infection in individuals, what sort of cross-variant immunity there is. Both from vaccine-derived immunity and infection-acquired immunity, the available studies suggest much lower protection against Omicron infection, pretty good protection against severe disease and death, but greatly reduced for infection. We'll have to wait and see whether that difference holds true for Omicron on Omicron by sub-variant, or even future variants, namely less protection against infection, but hopefully more protection against severe disease and death.

That issue will have a profound effect on what the fall and winter may look like, as we do expect waning immunity, both from vaccines and infection-acquired immunity, plus indoor exposure and opportunities for transmission, that there should be increased transmission potential in November, December, and January, and the extent to which there is long-range protection from severe disease and death will have a marked effect on outcomes.

May 16, 2022 - US reaches 1 million COVID deaths

As the United States reaches this somber milestone, IHME director Dr. Christopher Murray reflects on the impact of COVID-19 around the world and how we can better prepare for future health threats.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

The US has officially surpassed the awful milestone of a million reported deaths from COVID. This is a number that I think very few of us thought would ever come to pass when the pandemic started to break in February of 2020. In fact, back then we thought a concerted response would mean that the number would be a tenth of that, or even less.

Now, the true number of deaths from COVID is even larger. We think, based on looking at excess deaths, it's probably closer to 1.3 million deaths that have already occurred in the US, but by either metric, it's a staggering number.

COVID has had a terrible toll, not just here in the US but around the world, with 6 million reported deaths and more than 18 million excess deaths; those deaths are distributed throughout the regions of the world and not just in North America or in Europe.

We've entered a new phase of the pandemic, a phase where Omicron is much milder and a large fraction of the world's population has been infected with Omicron. The Omicron story has still to play out in China and North Korea, but in general we're entering this phase where people are going back to pre-COVID levels of interaction. Mask use is declining dramatically, and I think that's going to be the new normal.

We will see continued Omicron transmission, and Omicron will come back in the winter if we don't see a new variant. But it's likely we will see a new variant, and so while we might think that the era of mandates and profound changes in behavior might be behind us, we certainly haven't seen the end of COVID-19.

We should be thinking about how we manage COVID-19 new variants as they emerge and the critical role of continued use of boosters, vaccinating those who are still willing to be vaccinated but haven't been, and the new tools that we have like Paxlovid and potential other antivirals as they come along. All those combined mean, even if we have a new variant, we don't expect it to be as bad as it has been, which is good news. But it should give us pause to recognize the threat that we live with in the future, for either some remarkable new variant that will break through our current tools entirely, or new pathogens and new pandemics in the future.

Hopefully, this extraordinary experience in the US will motivate the US government and other governments to invest in greater capabilities to respond to new threats; detect them earlier; have a more rational, thoughtful, but rapid response to those threats as they emerge; and then to figure out who are most vulnerable, whether it's the groups that are essential workers, or those that have some sort of comorbidity, or those that are elderly. Whatever it may be for a new threat, it's critical that we learn about protecting the most vulnerable for future rounds of threats as they emerge.

At this terrible milestone, it is an opportunity for us to reflect both on what went wrong and how we can solve and prepare ourselves better for future rounds of COVID and future threats.

May 12, 2022

Key takeaways:

- East Asia: As rapid transmission of Omicron unfolds in Taiwan, it seems inevitable that an outbreak will also occur in China. However, it is impossible to predict when that may occur as it depends on how long the government chooses to continue pursuing a zero-COVID strategy.

- United States: Cases are increasing, particularly in the Northeast and on the West Coast, due to returning pre-COVID behavior patterns.

- Short-term: We predict a small peak in May to early June, but no major surge until the winter.

- Long-term: We predict as many as 30% of the US population will get infected through the winter with Omicron due to declining immunity. However, we expect the consequences to be much, much lower because of antivirals.

- Global: Data from South Africa do not indicate that BA.4 and BA.5 will lead to a major global surge. Our recommended strategy for dealing with COVID on a global scale is securing access to antivirals for all.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Omicron and the zero-COVID strategy in East Asia

Last week in IHME’s updated forecasts, we certainly were trying to take into account what’s unfolding in East Asia with continued rapid expansion of the Omicron epidemic in Taiwan, and that continues to expand. There’s this very challenging question of how Omicron will play out in China. The government is pursuing their zero-COVID strategy with lockdowns as needed.

We have been expecting Omicron, since February, in our modeling to eventually break through these efforts because it has appeared that control efforts on Omicron have been generally less successful around the world than for previous variants. So far, these strict lockdown policies have kept Omicron numbers at a relatively low level.

It's extremely hard to understand how the policy environment will play out in China. If they pursue strict lockdowns, it's possible they will keep Omicron transmission at a relatively modest level through to the fall. We do believe that it is inevitable there will be a large Omicron outbreak at some point in China, because maintaining a strict zero-COVID strategy is probably unsustainable as the year progresses, but it's impossible to know when that change in policy will occur.

Increasing cases in the United States and predictions for the winter

In the US, we're seeing increases in a number of parts of the country, particularly the Northeast, and some of the West Coast, in cases and hospital admissions. This is a pattern that follows what we’ve seen in Europe as people's behavior goes back to pre-COVID levels, and there is a little bit of transition to BA.2 and perhaps BA.4 and BA.5 as they continue to spread.

We do expect a modest increase in numbers. Our expectation is they will peak sometime in May or early June and then go back down. We don't expect a major surge from that. There have been reports from the White House of their efforts to model in the long term a large surge in infections.

In our long-range models, which we do not release publicly, we do expect in the winter a return Omicron surge. Of course if there's a new highly infectious variant that's more severe, that would trump this pattern we expect. We expect a surge in the winter because of declining immunity from exposure to Omicron, as well as declining immunity from vaccination and perhaps not as high a rate of repeat boosters as we've seen for the third dose, going into the future. The consequences of a winter surge in the US should be much smaller because of Paxlovid and increasing availability of antivirals and use of antivirals.

We certainly expect quite large numbers in the winter, not so much in the fall – perhaps as many as 30% of the US population getting infected through the winter with Omicron. But we expect the consequences to be much, much lower because of antivirals.

We don’t expect much in the way of government mandates, given the much lower ICU admission rate and death rate that should occur with these new strategies, particularly antivirals.

Global strategy should be ensuring access to antivirals for all

At the global level, there's been ongoing debate and concern about BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. There’s not an exponential surge there; there's a very slow increase in numbers. We so far are not seeing any indication that BA.4 and BA.5 could be the driver of a major global surge in cases, but of course this warrants monitoring on a regular basis.

Overall, in terms of general strategy globally, we've seemingly maxed out globally on the number of people who are unvaccinated that want to be vaccinated – as far as we can tell from the data, only about 3% of the world wants a vaccination that hasn’t received one. A lot of that is concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, but still it's not a large percentage of the population.

Perhaps the main strategy to deal with future variants is making sure that anyone who needs antivirals will get access to antivirals. There's a lot in that, both in terms of production of Paxlovid and health system infrastructure, and response patterns so that when somebody needs it, they can get it whether they're in a low-resource or high-resource setting. Those are our main observations on the epidemic as it continues to unfold.

May 9, 2022

Key takeaways:

- Global: Mortality from COVID-19 is the lowest since April 2020.

- 3.1% of the population who wants a vaccine has still not received one, most in Africa.

- We must ensure equity in distribution of antiviral medication.

- Eid El-Fitr celebrations in Islamic countries could lead to a small increase in cases.

- United States: Reported cases and hospitalizations are increasing. We predict an additional 29,000 deaths by September.

- Home testing and delayed reporting of infections has made it more difficult to track COVID-19.

- We recommend: continuing surveillance for new variants, securing antiviral medication, preparing to return to mask use and physical distancing if another variant arises.

- China: The large percentage of elderly and unvaccinated people makes the population very susceptible to high mortality rates and overwhelmed hospitals if the zero-COVID policy fails.

- The current rise in Taiwan and previous surge in Hong Kong are warning signs of what could happen.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Projections and recommendations for the United States

We have increased our projections to September 1. Right now in the United States we are projecting 1.02 million deaths by September 1. That's an additional 29,000 deaths from May 2, when we ran our programs.

For the United States, the recommendations remain the same:

- We need to continue our surveillance and make sure we are doing enough sequencing to know what variants are circulating in the United States, and if BA.4 and BA.5 are being introduced in the US and how fast they are spreading.

- At the same time, we need to ensure that we have enough antiviral medications in order to distribute them. We know from their clinical trials that they reduce hospitalization and mortality, and they will reduce the pressures on our hospitals.

- Third, which is very important, if we are seeing a rise due to another variant in the United States, we should go back to wearing masks and physical distancing.

In the United States we are seeing an increase in reported cases and hospitalizations. In some states, we are seeing the rate of increase in admissions to hospital is much higher than the rate of increase of reported cases. We believe that's due to the fact that many people are testing themselves at home and not reporting to their counties and not using the local labs, so we are not capturing these cases.

BA.4 and BA.5 under study in South Africa

We are monitoring closely what's happening in South Africa, the infections with BA.4 and BA.5. We don't know yet if they are immune escape and they are infecting people that have been previously infected by BA.2. It's too early to tell, and the fact that many people in South Africa have been infected by Omicron 4-5 months ago, it's possible that the waning immunity is resulting in the infection from BA.4 and BA.5.

Chinese population remains susceptible, relying on zero-COVID policy

At the global level, mortality from COVID-19 is the lowest since April 2020. The global trends are mainly dominated by what's happening in China. Right now we are seeing a rise in cases in Taiwan. China is continuing with its zero-COVID policy and we feel that they will be able to control COVID-19 for a while. However, the economic pressure may not allow them to continue with such a policy.

If what we are seeing happen right now in Taiwan, or what happened previously in Hong Kong, will happen in China, we project a lot of mortality, unfortunately, and the surge will overwhelm the hospitals. Many older Chinese people are not vaccinated at the same level as other countries, and also the vaccines used in China are less effective than the vaccines used elsewhere, mRNA vaccines. So we would expect a major surge and a rise in mortality in China.

Vaccine and antiviral equity: we are not safe until all of us are safe

Based on vaccination rates and our monitoring of people who are willing to take the vaccine, we estimate right now that about 3.1% of people globally who want to get the vaccine and are willing to get the vaccine, have not received it. The majority of them are in Africa. We need to make sure that people who want to get the vaccine are receiving them, who failed distribution, which countries should support poor countries to get the vaccine and vaccinate their population. Again, we're not safe until all of us are safe.

The most important thing moving forward right now globally is to ensure that the global distribution, like with vaccination, that global distribution for antivirals is going forward and countries can secure what they need from antiviral in order to provide it to people who are infected, to reduce hospitalization and mortality.

Projections in Islamic countries following Eid El-Fitr

We are not projecting a rise in cases in the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean region, WHO region, but we are concerned in many Islamic countries after Eid El-Fitr celebrations with all the mobility, and people are visiting each other and celebrating the holidays. It's possible in some of these countries the decline will slow down and it's possible in some countries that we'll see a small surge in the coming weeks due to the holidays and the celebration.

Challenges with data collection

At IHME, with our projections, our major challenge in the coming months is the delay in reporting. Many countries and many states have moved to weekly reporting and it's very hard for us to monitor the situation. The fact in the United States that many people are testing themselves at home and not reporting their infections to the local health departments is making it hard for us to follow the epi-curve.

We are using admissions to hospitals, COVID-19 admissions, as our main indicator and some places like the United States, where we believe many people are testing themselves at home and not reporting those results to their local health department, we have lowered the infection-detection rate in order to make sure we'll be able to monitor these trends.

April 29, 2022

Key takeaways:

- Omicron will continue to spread in China. After already reaching Beijing, Omicron will likely continue transmission despite the government’s indication that they will keep pursuing the zero-COVID strategy.

- Cases are increasing in Delhi, India, and South Africa. The question remains: are the increases due to new, more transmissible sub-variants, or waning immunity from the previous Omicron wave?

- A concerted policy push is needed to increase access to antivirals. IP waivers have been given to 22 countries by Pfizer, and now a rapid scale-up in production must follow.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

This week from IHME we are not releasing a new set of projections yet. With few exceptions, the epidemic is still continuing to track our forecasts from earlier in the month. The key areas to pay attention to right now are, first and foremost, what's happening in China with the Omicron wave spreading, most importantly to Beijing. Many other cities within China apparently are also under lockdowns or partial lockdowns.

As we have been noting for months pre-Olympics, it's really a question of time when Omicron will spread more widely in China, given how transmissible it is, given the comparatively lower efficacy of the vaccines used in China, and particularly this issue that the zero-COVID strategy may not actually work. But our understanding is that the government will pursue that strategy vigorously, at least until the fall. So, no real change in expectations there, but it simply will be a challenging question as to whether that strategy can hold out until the fall.

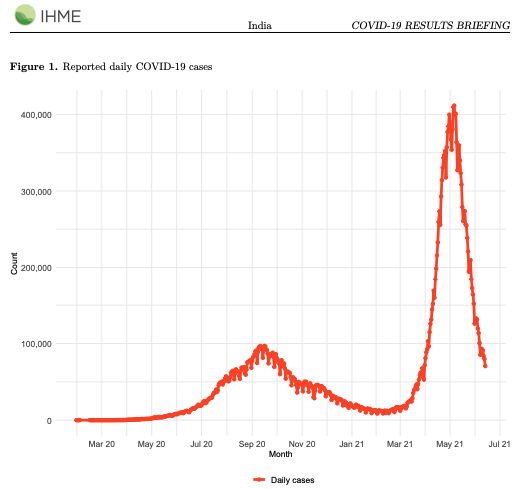

Increasing cases in India

The second area of concern that people have been tracking has been the steady uptick in cases in Delhi, India. The question is whether this is due to declining immunity from the prior Omicron wave or the possibility of one of the sub-variants of Omicron fueling transmission in Delhi. They have re-imposed their mask mandate, so we’ll see if that has some effect on that one part of India and the surrounding state of Haryana having some increased transmission.

BA.4 and BA.5 variants in South Africa

The third area of concern is the uptick in South Africa associated with the BA.4 and BA.5 sub-variants, a steady increase but not exponential. The question remains – is that because these sub-variants are more transmissible, or is it because they have immune escape over BA.1 and BA.2, which were there in South Africa and had become the predominant variants, or is it because of waning immunity, just through time. We are now, for South Africa, pretty much four months, or even four and a half in some provinces, after the peak of the Omicron wave.

Access to antivirals

The other main consideration globally around managing COVID, particularly in China and for the world, when new variants that are potentially more severe emerge, is access to Paxlovid. We’ve started to finally see some policy discussion around the importance of availability and access to Paxlovid. IP waivers have been given to 22 countries by Pfizer, and the question is, will there be more rapid scale-up in production? We strongly believe that needs a concerted policy push, equivalent to the efforts to expand vaccination. We will certainly expect more from IHME as we run our models in the near future to reflect any new updates in the data as we’ve been describing.

Do you have a question about IHME's COVID-19 modeling? We’d love to know what you’re wondering about.

Due to the sheer volume of questions we receive and our research team’s dedicated efforts in modeling the impact of Omicron around the world, we will only be able to address a limited number of questions. For media inquiries, please contact [email protected].

April 25, 2022

Key takeaways:

- New modeling suggests antivirals will be key to save lives during future surges. We are investigating the potential impact if a future variant were to be as severe as Delta with the transmission level of Omicron, and have found that antivirals make a profound difference.

- Cases are rising in the eastern United States, but deaths are not. Access to antivirals plays a key role in the low death rate.

- Still unknown if lockdowns will prevent an Omicron surge in China. Low vaccination among the 80+ population could result in a huge death toll if an outbreak occurs.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Lockdowns and Omicron in China

This week from IHME, we have not rerun our models. We have been spending time trying to understand the epidemic province by province in China. The key thing there as the outbreak continues to unfold in Shanghai with very broad-based transmission, is now reports of lockdown are confirmed by mobility data in many other cities within China. It remains to be seen whether the zero-COVID strategy will work to keep COVID, or the Omicron variant, from spreading very widely in China.

What we do know is that vaccine coverage in the 80+ population in many provinces is quite low. If Omicron spreads widely, there is a real risk that what we saw in Hong Kong could re-occur in mainland China. That's something that we are watching very closely. Currently, our models are assuming that the success that China's had with the zero-COVID strategy controlling Omicron in February, around the time of the Olympics, could be replicated, but we're also hearing reports that the economic costs of this are rising.

Cases on the rise in eastern United States

For the United States, we're seeing rising case numbers in a number of eastern states. There's some suggestion of rising case numbers in other states as well. There has not been a precipitous rise in case numbers yet – this increase looks to be related to continued relaxation of behavior, combined with the BA.2 sub-variant. The good news there is we're not seeing an increase in deaths. But it does point out how critical in the US – and pretty much everywhere – access to antivirals is going to be.

New modeling suggests antivirals will be key to save lives during future surges

While there continues to be a lot of discussion about access to vaccines in low- and middle-income countries and even discussion around boosters, there's perhaps not enough focus on making sure that people who need these highly effective antivirals like Paxlovid [can get them] in the future. This is somewhat important right now for the BA.2 sub-variant, but could be extremely important in the future as we imagine that there will be more infectious and potentially more severe variants that emerge during the course of this year.

We have started to do some modeling of what would happen if a variant that was as severe as Delta came along with the transmission potential of Omicron, and in that setting, widespread access to an antiviral like Paxlovid really makes a profound difference in saving lives around the world. So a very high priority, both in the US and everywhere in the world, for thinking about health system delivery strategies and access to the drug itself, is that those who can benefit from an antiviral are going to get that antiviral.

Expect more from us in the coming weeks as we continue to track the pandemic and try to model out how future scenarios unfold, both with what we know is currently occurring, but also potentially the emergence of new variants.

Emergence of new sub-variants

The last comment is on the emergence of the BA.4 and BA.5 sub-variants in South Africa. They are replacing BA.2 and there is some increase in case numbers, but still modest so far, as distinct from what happened with BA.2. We're now four months or more into the peak of Omicron transmission, so some of that increase in BA.4 and BA.5 could be from waning immunity from what was established through the early Omicron wave in November and December in South Africa. But it’s clearly another facet of the epidemic that will bear close monitoring.

April 14, 2022 - Update from Dr. Ali Mokdad

Key takeaways:

- BA.2 surge is ending in Europe. Cases are expected to continue declining in the Northern Hemisphere until next winter.

- Omicron in China: With only 2% of the population previously infected and 30% immune from vaccination, a large surge is expected if lockdown and strict control measures fail.

- BA.2 in the US: Some states are seeing a small rise in cases, but high levels of immunity due to previous infection (76%) are preventing a large surge.

- Mask wearing is below 25% – the lowest since we began tracking.

- Sharing antivirals and vaccines with countries in need is imperative.

- Policy recommendations:

- Secure and distribute antiviral medications.

- Maintain surveillance systems to detect new variants.

- For those who are immunocompromised or have high risk factors: continue wearing a mask and avoiding large crowds, especially indoors.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

Cases are declining in Europe

Globally, we are seeing a decline in reported cases in the majority of countries, and the short surge that has happened after the Omicron surge in some European countries is declining. So we see a decline in reported cases right now in the UK, in Germany, in France. In the long run, we believe that the number of cases will keep declining all the way to next winter in the Northern Hemisphere.

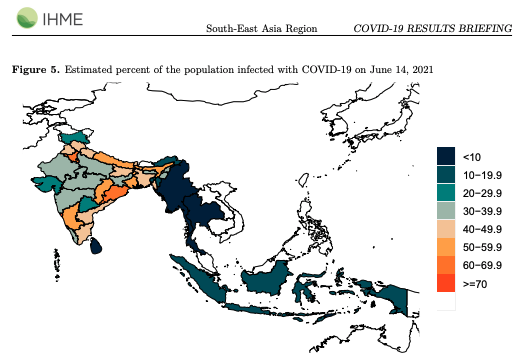

Surge predicted in China if precautions fail: only 30% of population currently immune

The situation we are monitoring closely right now is what’s happening in China. We believe the strict measures and the lockdown in China have been successful so far in containing the spread of the virus, but with Omicron being extremely contagious and spreading much faster than any previous variant we have encountered, we don’t believe that China could contain the spread of Omicron for a long time. So we’re expecting a rise of infections, reported cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in China if these measures that are in place right now are not successful in containing the spread of the virus.

The reason we believe that for China – if you look at measures that China put in place, they were so effective at preventing infection. Right now in China, about 2% of the public has been infected by COVID-19 since the beginning of COVID-19, compared to 76% of us here in the United States. So we have more immunity than people in China, we have better vaccines with mRNA, and we have a higher vaccination rate, especially among the elderly population. Not for the general population, but for the elderly population in the United States we have a higher vaccination coverage.

So when you put all of these together, in the United States we have about 73% of the public that is immune to Omicron, compared to 32% in China. So any outbreak in China, simply because there are about 70% of the public in China that are susceptible to Omicron, we expect a rapid surge of cases, similar to what we are seeing in Hong Kong and in other countries as well.

Mobility is increasing, while mask wearing and testing decline

More countries are relaxing their mandates right now – for example, New Zealand and Australia opened their borders to each other and travel is allowed right now. This could have an impact on reported cases as people are traveling and feel they are free to travel right now.

Mask wearing is the lowest since we started reporting on mask wearing and since IHME started promoting mask wearing and providing scenarios showing how effective masks are in preventing mortality. So we're at less than 25% right now when it comes to mask wearing – it varies by countries, but mask wearing has dropped a lot because many countries relaxed their mask mandates, especially in Europe.

Testing is declining in many countries: for example, in the UK, they're not paying anymore for testing, so we're seeing a decline in testing. That will impact our ability to track the pandemic in many countries and many locations. Some countries and states have decided to release data on a weekly basis, not on a daily basis, so the quality of data, the timeliness of data has changed, and that will impact our ability to track – not only us, but other groups who are doing similar projections – our ability to track the pandemic moving forward.

Sharing antivirals and vaccines with countries in need is imperative

Globally, there is a need to secure more antiviral medication and make sure it is available to every country to save lives and to prevent overwhelming the hospitals and protect the medical system. In countries where we see a surge of cases, recommending people to wear a mask and observe physical distance will be important. And in many countries in the world, it's very important to encourage the public to receive the vaccines, especially those who are not yet vaccinated and those who are immunocompromised and have health conditions.

Our data right now show that a small percentage of people globally who want to get a vaccine or are willing to take the vaccine have not been able to receive the vaccine. The majority are in Africa. Therefore, it's very important to share vaccines with countries where people are willing to take the vaccine and they're waiting to get their vaccine. This is the only way for all of us to save lives and stop the spread of the virus, and of course we're not safe until all of us are safe.

In the United States, the BA.2 variant is causing small rise in cases, but no surge expected

In the US, we are seeing a slight rise in reported cases in some states, but we don't expect a surge similar to what we have seen in some European countries here in the US, simply because in the United States we have more immunity due to higher rates of previous infections in the country. BA.2 right now is the main circulating variant here in the United States – about 86% of the variants that are circulating in the US are BA.2. But because of previous infections in the US and our immunity, we don't expect a surge similar to what we have seen in Europe.

The extension of the mask mandate on public transportation at the federal level and on airplanes will help a lot, especially right now with spring break vacations and people traveling. Many families are traveling for the first time with their children right now since the start of the pandemic, so one would expect, with the increased mobility and the fact that mask wearing is less than 25% in the US, that we'll see a slight increase in reported cases in the United States.

We still believe that the pandemic phase of COVID-19 is over, simply because we have higher infections here in the United States and hence higher immunity. We are improving our vaccine and we soon should be able to have vaccines that are designed for the new variants; the vaccines that we have right now are highly effective, but we need to remember they were designed for the [ancestral] variant. And of course we have antiviral medications that will save lives and prevent hospitalization. If there is a surge from an escape variant, we can always go back to physical distancing and mask mandates and ask the public to wear a high-quality mask and avoid large gatherings.

Recommendations for controlling the virus in the US

The recommendations in the United States to contain the virus and the epidemic of this virus in the country remain the same: secure antiviral medications, distribute them, make sure patients can access them in a short time to save lives and prevent overwhelming our hospitals; maintain our surveillance system and also our genetic sequencing to know what variants are circulating in the US and, if there is a rise in cases, where it's happening and among whom, especially if they are vaccinated or not, so we can tell as soon as possible if the new variant is an escape variant and the vaccines are not as effective against it.

For the public who are immunocompromised or have high risk factors, they need to remain more vigilant and wear a mask, especially if they are in close indoor settings with a large crowd. And all of us, if there is a surge and a new variant that is circulating, we also need to put our masks back on and make sure we maintain a physical and safe distance in order to reduce the chance of getting this virus. In the short term, the coming few months in the United States, IHME is projecting a decline after this tiny little surge, a decline of cases all the way until next winter, short of a new variant appearing. But we are projecting a decline in the number of cases all the way until next winter.

April 8, 2022

Key takeaways:

- New prediction for China: no major Omicron surge. Provinces continue zero-Covid strategy, adhering to strict lockdown measures whenever there is an outbreak. By incorporating lower mobility into our model, we no longer see a massive surge in the forecasts for the coming months.

- BA.2 is declining in Europe and is not expected to cause a major surge in the US. Other countries around the world may also avoid a surge due to previous high levels of infection from Omicron.

- Access to antivirals should be the primary focus of global efforts, shifting from previous emphasis on vaccination.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

BA.2 is on the decline in Europe